Heartworm 102 – Prevention & Testing

Click here for Part I.

In the last article, we talked about what heartworms are and how they affect pets. You might check that one out first if you missed it, as a basic understanding of the life cycle is helpful in understanding today’s topics – prevention and testing.

Prevention Strategies

I’m forever the skeptic, so I’ll admit if someone told me I needed to buy pills for my pets every month for life I’d be the first to scan their eyes for dollar signs – veterinarian or otherwise. I certainly understand when the occasional client looks at me incredulously, or asks about just giving during the summer. But we aren’t making this stuff up – with a little understanding of preventatives and the biology of disease, you should agree.

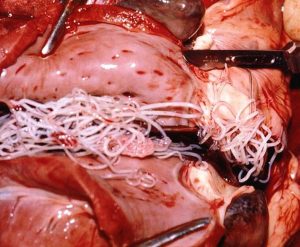

First off, it’s worth noting that we’re generally talking about preventing disease, not infection. The major problem with heartworms are adults (cats are a bit different, but we’ll address that in the last article), and it takes about six months for them to mature after infection. The microscopic larvae that cause initial infection are susceptible to low doses of certain anti-parasite drugs, so the idea is that by giving pets a dose at regular intervals we can stop the disease (adult worms) from developing, even if we haven’t stopped infection per say. That’s good, because as anyone who’s been to Louisiana in July will tell you, it’s bloody near impossible to keep from getting a bitten by mosquitoes no matter what you do. And it only takes one.

So, why monthly instead of every six months? That’s how long it takes to get adults, right? Well, the trouble is that as they age, larvae develop resistance to those relatively safe anti-parasite drugs. Effectiveness gets unpredictable 4-5 weeks after infection, and eventually they become pretty impervious to those drugs. We have to resort to drastic measures to kill adults – in fact, the standard treatment for adult infection is in the arsenic family. So monthly dosing is the safest bet (and a lot easier to remember). On the flip side, it’s worth noting that if you miss a dose by a week or two you’ll probably be okay. No guarantees, but it makes for easier sleeping when life (or memory) inevitably mucks with your schedule.

And why every month? Mosquitoes don’t wear snowshoes, right? I could tell you that “heat islands,” warm areas near houses and the like, may create microenvironments where mosquitoes can hatch even in the winter. I could tell you it only takes one infected mosquito to threaten the life of your pet. I could tell you many preventatives have important benefits other than just heartworm protection, and I’ll discuss those below. All are true, but I’ll level with you. Even if I could guarantee your pet wouldn’t see a mosquito until April 1st or after October 31st (I can’t), I know most of us – myself included – would forget to start until sometime in May or miss that last dose in the fall. And say you snowbird it somewhere warm for Christmas – what then? It’s just easier to be consistent if you’re on a consistent schedule. And where heartworm is concerned, consistency can save pets’ lives.

Types of Preventatives

The currently available preventatives fall into three broad categories – monthly oral or topical products, and one injectable product that’s given every six months. All of these are valid, effective choices for heartworm prevention; the main difference between products is what they cover in addition to heartworm.

Most oral and topical products have additional anti-parasite drugs that worm your pets monthly for GI parasites they’re likely to get into, such as roundworms and hookworms. This is actually another big argument for monthly preventatives, as those are parasites people can get – specifically, those small people who rarely wash their hands and like to suck on their fingers after playing with the dog. Roundworms would likely survive a nuclear fallout, so they can certainly infect your pet in the middle of winter, and that monthly “heartworm pill” is a good way to keep them from infecting your three-year-old in turn.

Certain products will cover additional parasites such as tapeworms, whipworms, and even fleas. To my knowledge no single product currently covers everything, so it’s worth talking to your veterinarian about what product or combination of products best covers the risks specific to your area and your pets lifestyle. I should also point out that’s the big drawback to the “heartworm shot” – it doesn’t provide monthly protection against all that other disgusting stuff pets tend to get into, just heartworm. It will kill off hookworms, but only every six months at the time the shot is given. For most dogs I recommend an oral heartworm product in addition to a topical flea-and-tick; for cats I usually recommend a topical product since getting an oral product in them can be a feat in itself.

Heartworm Testing

Yes, your dog should be tested for heartworm yearly even if you give monthly preventatives.Nothing is 100% effective, and disease caught early and treated early does far less harm. There are many scenarios that might lead to treatment failure, such as:

- You miss a dose for whatever reason. This is by far the most common situation – heck,I’ve missed doses.

- Your pet has some indigestion and throws up the pill, unbeknownst to you.

- Your pet goes swimming shortly after a dose, or another pet grooms it off them.

- The medication has been mishandled and has lost its effectiveness. Heat can destroy most drugs – say, you forgot and left it in the car for a few summer days, or you bought it from somewhere other than your veterinarian and it was inappropriately handled (that’s a whole other can of worms, and the subject of a future article).

There has also been some concern over possible resistance developing to the drugs we use; at this point reports of “treatment failures” are few, and I’m fairly sure most could really be traced back to one of the above reasons. However, realistically we have to expect that some degree of resistance will develop eventually.

It’s worth noting the standard heartworm test looks for the presence of adult female worms. Think back to the first article where we discussed the parasite’s life cycle and you will realize this means the test won’t be positive until at least six months post infection. Likewise, if there are only a few worms and all are male, the test would be negative as well – I don’t generally recommend regular testing for cats partially due to this, but we’ll come back to that in the last article. It’s complicated. So, to summarize – all pets should get monthly preventatives (or the six-month shot for dogs), and dogs should be tested annually. Hopefully it’s clear now why that’s in their best interest. In the final article, we’ll talk specifically about heartworms and cats. They have some unique concerns and complications – as a professor liked to remind us back in school, “they aren’t just small dogs.”